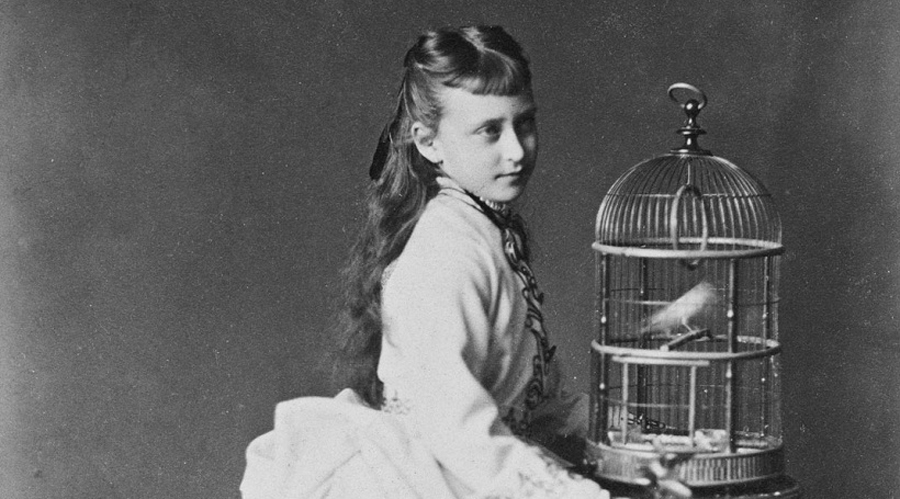

Not every generation is destined to meet along its path such a blessed gift from heaven as was the Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna for her time, for she was a rare combination of exalted Christian spirit, moral nobility, enlightened mind, gentle heart, and refined taste. She possessed an extremely delicate and multifaceted spiritual composition and her outward appearance reflected the beauty and greatness of her spirit. Upon her brow lay the seal of an inborn, elevated dignity which set her apart from those around her. Under the cover of modesty, she often strove, though in vain, to conceal herself from the gaze of others, but one could not mistake her for another. Wherever she appeared, one would always ask: "Who is she who looketh forth as the morning, clear as the sun" (Song of Solomon 6:10)? Wherever she would go she emanated the pure fragrance of the lily. Perhaps it was for this reason that she loved the colour white—it was the reflection of her heart. All of her spiritual qualities were strictly balanced, one against another, never giving an impression of one-sidedness. Femininity was joined in her to a courageous character; her goodness never led to weakness and blind, unconditional trust of people. Even in her finest heartfelt inspirations, she exhibited that gift of discernment which has always been so highly esteemed by Christian ascetics.

The grand duchess herself acknowledged that a great influence on the formation of the inner, purely spiritual side of her character was the example of a paternal ancestor, Elizabeth Turingen of Hungary, who through her daughter Sophia was one of the founders of the House of Hesse. A contemporary of the Crusades, this remarkable woman reflected the spirit of her age. Deep piety was united in her together with self-sacrificing love for her neighbour, but her spouse considered her great beneficence squanders and at times persecuted her for it. Her early widowhood compelled her to lead a life of wandering and need. Later she was again able to help the poor and suffering and completely dedicate herself to works of charity. The great reverence which this royal struggler enjoyed even during her lifetime moved the Roman Catholic Church in the thirteenth century to number her among its saints. The impressionable soul of the grand duchess was captivated in childhood by the happy memory of her honoured ancestor and made a deep impression on her.

Her rich natural gifts were refined by an extensive and wide education which not only satisfied her mental and esthetic needs but also enriched her with knowledge of a purely practical nature, essential for every woman with household duties. "Together with Her Majesty (i.e., Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, her younger sister) we were instructed during our childhood in everything,'' she once said in answer to how she became acquainted with all the details of housekeeping.

Chosen as the future wife of the Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, the grand duchess arrived in Russia during the period when the country, under the firm rule of Alexander III, attained the blossoming of its might in a purely national spirit. With her moral sensitivity and inborn love for knowledge, the young grand duchess began an intense study of the national characteristics of the Russian people and especially of their faith which places a deep mark on both their national character and upon all of their culture. Soon Orthodoxy won her over by its beauty and inner richness which she often would contrast with the spiritual poverty of Protestantism. ("And they are so self-satisfied about everything!" she said about Protestants.)

The grand duchess, of her own volition, decided to unite herself to the Orthodox Church. When she made the announcement to her spouse, according to the account of one of the servants, tears involuntarily poured from his eyes. Emperor Alexander III himself was deeply touched by her decision. Her husband blessed her after Holy Chrismation with a precious icon of the Savior, "Not Made by Hands" (a copy of the miraculous icon in the Chapel of the Savior), which she treasured greatly throughout the remaining course of her life. Having been joined to the Faith in this manner, and thereby to all that makes up the soul of a Russian, the grand duchess could now with every right say to her spouse in the words of the Moabite Ruth, "Your people have become my people, and your God my God" (Ruth 1:16).

Even during these years, she dedicated much time to philanthropic activities, though this was considered one of the main obligations of her high position and therefore did not earn for her much public merit. As part of her social obligations, the grand duchess was forced to participate in social life which was already beginning to oppress her because of its frivolity. The terrible death of the grand duke Sergei Alexandrovich, who was torn apart by a bomb in the holy Kremlin itself (near the Nicholas Palace where the grand duke had moved after he left his position as Governor-General), began a decisive moral change in the soul of his spouse which caused her to forsake her former life once and for all. The greatness of spirit with which she endured her trial evoked for her the deserved admiration of everyone. She even found in herself the moral strength to visit Kaliev, the murderer of her husband, in the hope of softening and healing his heart by meekness and complete forgiveness. These Christian feelings she also expressed, through the person of the slaughtered grand duke, by having the following touching words of the Gospel inscribed upon the memorial cross, erected according to the plans of Vasnetsov, at the site of his death, ''Father, forgive them for they know not what they do..."

However, not everyone was capable of understanding the change which had taken place in her. One had to live through such a staggering catastrophe as this, in order to be convinced of the frailty and illusory nature of wealth, glory and the things of this world, and about which for so many centuries we have been warned by the Gospel. For the society of that time, the decision of the grand duchess to dismiss her court in order to leave the world and dedicate herself to serving God and neighbour seemed like scandal and madness. Despising both the tears of friends, gossip and mockings of the world, she courageously set out on her new path. Having earlier chosen for herself the path of the perfect, i.e. the path of ascetic struggle, she began with wisely measured steps to ascend the ladder of Christian virtues.

The extended period of mourning for the grand duke, during which she retired into her interior world and was continually in church, was the first real break to separate her from what up until then had been her normal everyday life. The move from the palace to the building she acquired at Ordinka, where she allotted only two very modest rooms for herself, signalled a full break with the past and the beginning of a new period in her life.

From now on her main task became the building of a sisterhood in which inner service to God would be integrated with active service to one's neighbour in the name of Christ. This was a completely new form of organized charitable Church activity and consequently drew general attention to itself. At its foundation was placed a deep and immutable idea: no one could give to another more than he himself already possessed. We all draw upon God and therefore only in Him can we love our neighbour. Natural love so-called or humanism quickly evaporates, replaced by coldness and disappointment, but one who lives in Christ can rise to the heights of complete self-denial and lay down his life for his friends. The grand duchess not only wanted to impart to charitable activities the spirit of the Gospel but to place them under the protection of the Church. Thus she hoped to attract gradually to the Church, those levels of Russian society, which up until that time had remained largely indifferent to the Faith.

The community was intended to be like the home of Lazarus which the Savior so often visited. The sisters of the convent were called to unite both the high lot of Mary, attending to the eternal word of life, and the service of Martha, to that degree in which they found Christ in the person of His less fortunate brethren. In justifying and explaining her thought, the ever-memorable foundress of the convent said that Christ the Savior could not judge Martha for showing Him hospitality since the latter was a sign of her love for Him. He only cautioned Martha, and in her all women in general, against that excessive fussing and triviality which draw them away from the higher needs of the spirit.

To be not of this world, and at the same time live and act in the world in order to transform it—this was the foundation upon which she desired to establish her convent. She put her whole heart into her beloved Martha and Mary Convent. It is not surprising that the convent quickly blossomed and attracted many sisters from the aristocracy as well as the common people. Nearly monastic order reigned within the inner life of the community and both within and without the convent her activities consisted in the care of those who visited the sick who were lodged in the convent, in the material and moral help given to the poor, and in the almshouse for those orphans and abandoned children found in every large city. The grand duchess paid special attention to the unfortunate children who bore within themselves the curse of their fathers' sins, the children born in the turbid slums of Moscow only to wither before they had a chance to blossom. Many of them were taken into the orphanage built for them where they were quickly revived spiritually and physically. For others, constant supervision at their place of residence was established.

The spirit of initiative and moral sensitivity which accompanied the grand duchess in all her activities, inspired and impelled her to search out new paths and forms of philanthropic activity, which sometimes reflected the influence of her first, western homeland, and its advanced organizations for social improvement and mutual aid. And so she created a cooperative of messenger boys with a well-built dormitory, and apartments for the girls who took part in this activity. Not all of these establishments were directly connected with the convent, but they were all like rays of light from the sun united in the person of their abbess, who embraced them with her care and protection.

At the beginning of the war, she gave herself over with complete self-sacrifice to the service of the sick and wounded soldiers whom she visited not only in the hospitals and sanitoriums of Moscow but also at the front. When the revolutionary storm broke out she met it with amazing self-control and calm. It seemed that she stood on a high, unshakable cliff, and from there fearlessly looked out at the waves storming around her and raised her spiritual vision to eternity.

She did not harbour even a shadow of ill feelings against the madness of the agitated masses. "The people are children, innocent of what is transpiring," she remarked quietly. "They are led into deception by the enemies of Russia." Nor was she depressed by the great suffering and humiliation that befell the royal family who were so close to her: "This will serve for their moral purification and bring them nearer to God," she noted once with radiant gentleness.

The charm of her whole temperament was so great that it automatically attracted even the revolutionaries when they first arrived to examine the Martha and Mary Convent. One of them, apparently a student, even praised the life of the sisters, saying that no luxuries were noticeable, and that cleanliness and good order were the rule, which was in no way blameworthy. Seeing his sincerity, the grand duchess struck up a conversation with him about the outstanding qualities of socialist and Christian ideals. "Who knows," remarked her unknown conversationalist as if influenced by her arguments, "perhaps we are headed for the same goal, only by different paths," and with these words left the convent.

"Obviously we are still unworthy of a martyr's crown," the abbess replied to the sisters' congratulating her for such a successful end to the first encounter with the Bolsheviks. But that crown was not far from her. During the course of the last months of 1917 and the beginning of 1918, the Soviet power to everyone's amazement granted the Martha and Mary Convent and its abbess complete freedom to live as they wished and even supported them by supplying essentials. This made the blow even heavier and unexpected for them when on Pascha the grand duchess was suddenly arrested and transported to Ekaterinburg. His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon attempted with the help of Church organizations to take a part in her liberation but was unsuccessful. Her exile was at first accompanied by some comforts. She was quartered in a convent where all the sisters were sincerely involved. Special comfort for her was that she was not hampered from attending services. Her position became more difficult after her transfer to Alapaevsk where she was imprisoned in one of the city schools together with her ever-faithful companion, Sister Barbara, and several grand dukes who shared her fate.

Nevertheless, she did not lose her abiding firmness of spirit and occasionally would send words of encouragement and comfort to the sisters of her convent who were deeply grieving over her. And so it continued until the fateful night of 5/18 July. On this night together with the other royal captives striving with her and her valiant fellow-struggler Barbara in Alapaevsk, she was suddenly taken in an automobile outside the city and apparently buried alive with them in one of the local mine shafts. The results of later excavation there has shown that she strived until the last moment to serve the grand dukes who were severely injured by the fall. Some local peasants who carried out the sentence on these people whom they did not know, reported that for a long time there was heard a mysterious singing from below the earth.

This was the great-passion-bearer, singing funeral hymns to herself and the others until the silver chain was loosed and the golden bowl was broken (cf. Eccles. 12:6) and until the songs of heaven began to resound for her. Thus the longed-for martyr's crown was placed on her head and she was united to the hosts of those of whom John, the seer of mysteries, speaks: "After this I beheld, and, lo, a great multitude, which no man could number, of all nations, and kindreds, and people, and tongues, stood before the throne, and before the Lamb, clothed with white robes, and palms in their hands;...And I said unto him, Sir, thou knowest. And he said to me, These are they which came out of great tribulation, and have washed their robes, and made them white in the blood of the Lamb" (Rev. 7:9, 14).

From: saintelizabethskete.org